The Amazing Survival of an Ancient Church

The Syriac Orthodox Church is one of the most ancient churches in Christendom and claims a presence in Jerusalem dating back to the time of Jesus. Ensconced in the Old City’s Armenian Quarter, only steps away from where the four quarters meet, the Syriacs are settled around the Monastery of St. Mark the Evangelist in a warren of small alleys that abut the Jewish Quarter.

The Monastery, which is comprised of two chapels, was first mentioned in the 6th century by the theologian John of Dara. Since 1471, it has been in the hands of the Syriac Orthodox Church, which purchased it from the Coptic Church. At the entrance is a sign that proclaims the monastery to be the site of the oldest church in the world. Amazingly, in 1940, while digging a grave in the church’s altar, a Greek inscription with the following text was uncovered:

‘This is the house of Mary, the Mother of John, who was called Mark. And it was proclaimed a church by the Holy Apostles in the name of the Mother of God, Mary, after the Ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ into heaven. It was built a second time after Jerusalem was destroyed at the hands of King Titus in the year 73 of the Christian era.

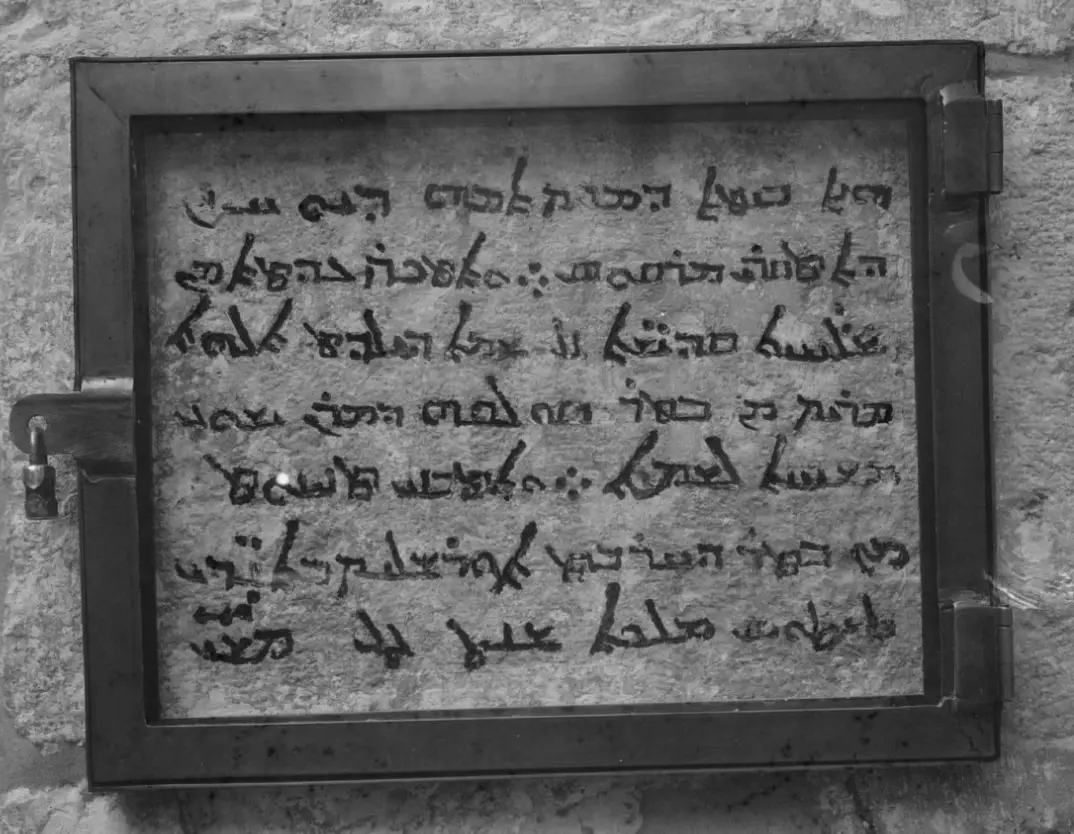

The inscription, which was written in “Estrangelo” Greek, was dated by the local bishop to the 5th or 6th century and is prominently displayed inside to the right of the church’s entrance. While there are some scholars who cast doubt on the authenticity of this inscription, this modest church is nonetheless associated with several important Christian traditions.

First, the house of St. Mark the Apostle (who was called John) is where the angel directed St. Peter after his miraculous escape from prison recounted in the Book of Acts (12:12). At the time, Mary, Mother of Go,d and some of the disciples took refuge here from the Romans. The inner door of the monastery is claimed to be the door that Rhoda opened when St. Peter knocked on it.

The chapel itself is richly adorned and contains some important artifacts, including a small baptismal wash basin in which Mother Mary was herself baptized as a child. According to tradition, Mary brought it with her and, to this day, the Syriac community baptizes their children in this basin.

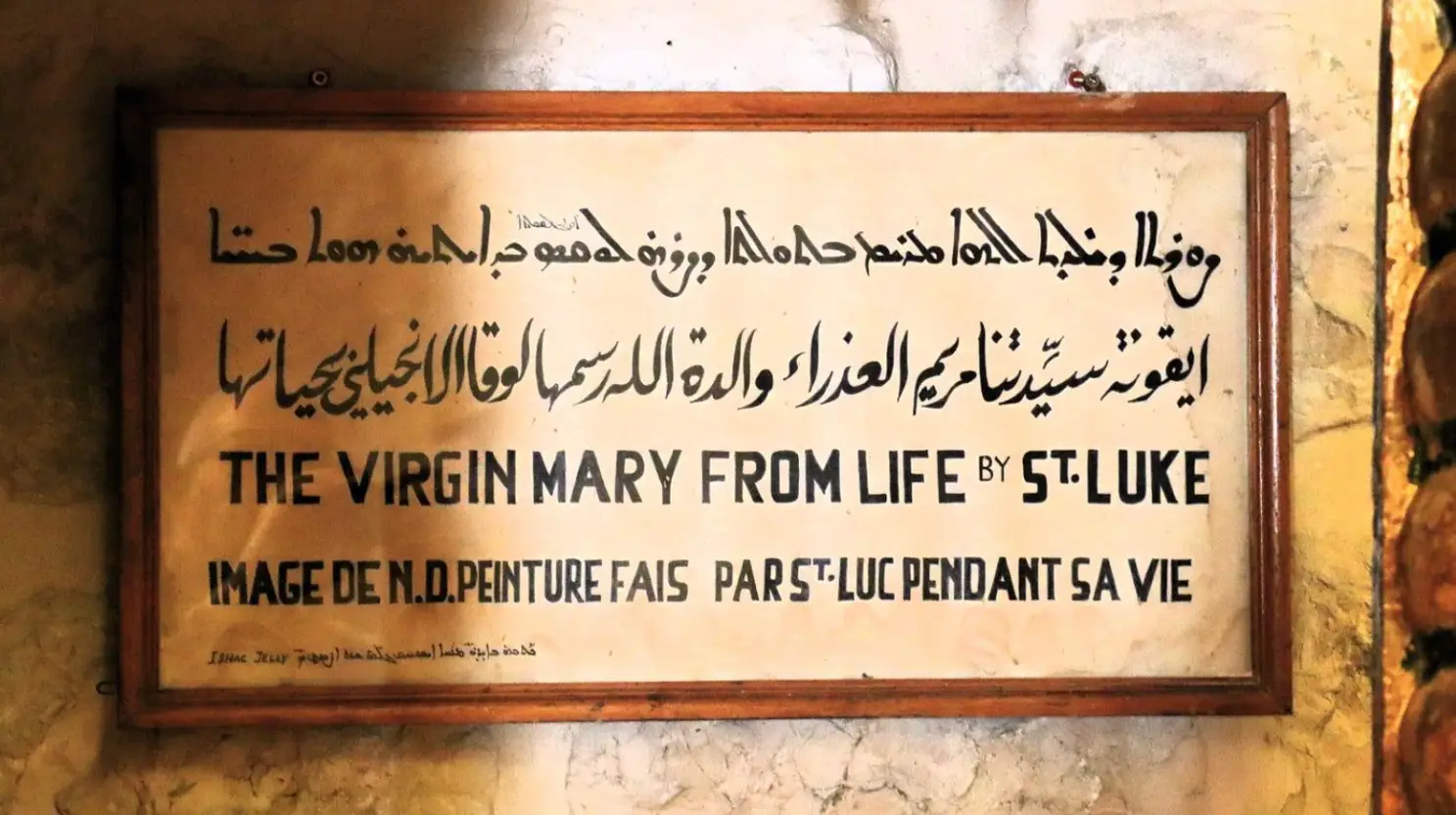

As if this weren’t remarkable enough, just above the wash basin is an icon of Mary and Jesus painted by none other than St. Luke the Apostle. After doing some research, I discovered that this was not so unique after all and that there are apparently dozens of such paintings by St. Luke scattered all over the world. In fact, there are so many of these paintings that there are even more than a few medieval paintings depicting St. Luke painting.

Nonetheless, considering that Mary and the disciples sojourned at this location, this particular painting may be one of the oldest surviving originals. Indeed, since St. Luke admits in the opening verses of his Gospel that he never actually met Jesus in person, the local tradition is that he learned about Jesus while painting this icon. While Mary sat for the painting, she told Luke about her Son, His teachings, and the miracles that He performed. This piqued Luke’s curiosity, which led him to personally investigate Jesus and, ultimately, to write his Gospel.

Though the chapel is reminiscent of an Orthodox Church (hence it is known as Syriac Orthodox), it does not have an iconostasis, but rather a curtain. A quick look, and it is clear that there is nothing written in Greek and that the priests dress in a manner more reminiscent of the Coptic Church.

The Bibles found in the church are known as the Peshitta, or plain text, and are written in the distinct Syriac alphabet of the Aramaic language. A dialect of this language, which was widely spoken throughout the ancient world at the time of Jesus, continues to be taught and spoken in the Syriac community to this day.

So, what kind of Christians are these? Are they Syrian Christians, or, as the street sign in the church’s alleyway states, are they Assyrian Christians? What are their doctrinal beliefs, and how many of them are there in Jerusalem and more widely around the world? As it turns out, there are no clear-cut answers to any of these questions.

For starters, since the founding of the modern state of Syria, the whole discussion of nomenclature has only become more confusing. A Syrian Christian could refer to someone who belongs to the Syriac Orthodox Church or simply be a Syrian Christian of any doctrinal stripe. In an attempt to minimize the confusion, since the year 2000, the term Syriac has replaced Syrian when referring to the church. Yet, among themselves (i.e. their endonym, to use an anthropological term), they go by the polysemous Suryoye or Suryoyo.

Of course, depending on your ideological views or where you are in the world, the church is known by other names. For example, for much of history, adherents of this faith tradition were known as Jacobites, after the 6th-century bishop and miracle worker Jacob Baradaeus.

A proponent of the non-Chalcedonian Miaphysite Christological doctrine, Baradaeus purportedly ordained 100,000 priests and single-handedly saved this faith tradition. Today, most (but not all) Syriac Orthodox prefer not to be called Jacobites because the term has a long history of being used pejoratively.

Oftentimes, Syriacs are confused with Assyrians. This is not only confusing because they sound similar, but also because both groups originate from lands that were once part of the Assyrian Empire. To further complicate matters, in the 20th century, a Christian nationalist movement surfaced that proposed a pan-Assyrian identity that incorporated other groups espousing Aramean, Chaldean, Assyrian, Syrian/Syriac, and Phoenician identities. While some members of these groups have enthusiastically embraced the Pan-Assyrian cause, most reject this overarching label and prefer to self-identify by their local appellations, much to the chagrin of the nationalists.

Assyrians, of which there are no more than a handful in Israel are based in northern Iraq and have their own separate church known as the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East. Historically, this church was widely distributed throughout Persia, Central Asia, India, Mongolia, and China. Known in the past as Nestorians, they prefer not to be called by this name since it was used pejoratively in the past. Though their name contains the word “Catholic” in it, they are not in communion with the Catholic Church. There are, of course, Assyrian Christians in communion with the Catholic Church who are known as Chaldeans.

So, what exactly distinguishes the Syriac Orthodox from the Catholic and the Orthodox? The question of Christ’s nature. Is it one nature, i.e. man and God with full humanity and divinity (aka Monophysite)? Or are there two natures of full humanity and divinity (aka dyophysite)?

The Syrian Orthodox Church argued the former, but rejected the term “Monophysite” i.e. of one nature, in favor of “Miaphysite”, which implied that this nature was mixed in the way that humans are a mix of their mothers and fathers. Ever since the Council of Chalcedon in 1451 rejected this proposition, the Syriac Orthodox Church – like the Coptic, Armenian, and Ethiopian churches – broke with the Roman Catholic church and are classified as non-Chalcedonian churches.

The Syriac church was severely persecuted for this doctrine in Byzantine times, but found an ally in Justinian’s wife Theodora and continued to grow, reaching its apogee in the 13th century. Following the Crusader capture of Jerusalem in 1099, Baldwin I invited Syrian Christians to repopulate the decimated Jewish Quarter of the Old City. Known today as the Muslim Quarter, in the 12th century, Syriac Christians flourished in what was known then as the Syrian Quarter.

The Syriacs built several churches across Jerusalem and even managed to wrangle a foothold in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. At the height of the Middle Ages, there were 103 bishoprics from Mesopotamia to Cyprus compared to only 26 today. The Mongol invasions of the 13th and 14th century wreaked havoc in the region and the church never fully recovered.

In the last century, Syrian Christians (of all denominations) suffered a genocide at the hands of the Turks known as the Sayfo (meaning “sword” or “extermination”). Less known than the Armenian genocide, the Sayfo happened at the onset of World War I in 1915 and resulted in the massacre of over 250,000 Syrian Christians. As of today, there are approximately two million Syrian Orthodox Christians spread all over the world. The patriarch officially is responsible for the See in Anthioch, but since 1915 is located in Syria – first in Homs and currently in Damascus since 1957. Last year, in June of 2023, a Syriac Orthodox Patriarch visited Jerusalem for the first time since 1967.

In Jerusalem, there are currently some 170 families with over 400 people. In addition to St. Marks, the Syriac community of Jerusalem conducts mass in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in the Chapel of St. Joseph of Arimathea and Saint Nicodemus, though ownership of the site is disputed between them and the Armenians. In Bethlehem, which is under Palestinian control, there are approximately 2,000 adherents and a beautiful church, located a short walk from Manger Square.

In 2014, following a public campaign on the part of the Maronite and Syriac community, the Israeli Ministry of the Interior provides interested citizens with the option of being listed as “Arameans” on their National Identity Cards. Prior to this, these communities were listed on their IDs as “Arab”.

Although both communities speak Arabic and embrace Arab culture, there were those in the community that felt strongly that this designation did not properly reflect their ethnic origins. They rightly pointed out that Arameans predate the arrival of Arabs to the region by over a thousand years and that, notwithstanding the fact that they know Arabic, they continue to educate their children in Aramaic and speak it to this day.

While this was at the community’s request and is not an obligatory mandate, it did not go over well in some corners of Palestinian society and was criticized at the time by the Greek Orthodox Church Patriarchate. It is true that any Israeli Christian can apply to be listed as Aramaic, but since knowledge of the Aramaic language is a prerequisite for this designation, perhaps 10,000 people are eligible in practice. This constitutes about 2% of Israel’s Christian population. To date, less than 1,000 people have been listed as Arameans on their national ID.

Lastly, as I was writing this, I read in the news of a terrorist act in which an Assyrian bishop and four others were brutally stabbed in Sydney, Australia. This reminded me that since the US invasions of Iraq, the majority of Syriac and Assyrian Christians have left for the west. In part, this was because of economic difficulties, but mostly it was because of Islamic extremism. For example, when ISIS captured large swathes of Iraq in 2014, Christian homes and businesses were required to be marked with the Arabic letter “noon,” the first letter of the word “Nasrani” or Nazarene (i.e. Christian) in an act reminiscent of the Nazis.

In terms of ideology and actions, Hamas is not much different from ISIS. Those who are providing Hamas with public support may, in part, be well meaning but I doubt that they appreciate the consequences of their actions. At the end of the day, Israel, with all its warts and faults, remains one of the very few places in the Middle East rich in cultural and religious diversity where minorities can prosper and live in peace.

Sign up to our mailing list and receive our newsletter with updates on upcoming tours, lectures, workshops, and courses.